Youth Community

Aid Ukraine

Order Why Israel Resources

Support our ministry

Subscribe newsletter

Israel & Christians Today

Biblical understanding about Israel

Iby Knill - The Woman Without a Number

By Marie-Louise Weissenböck (Chair C4I Austria).. When my husband and I visited Iby Knill, a nearly 92-year-old woman, on 12 September 2015 in her home in Leeds, England, a long-cherished wish of mine was fulfilled. Her moving memories were disclosed for the first time in 2010, when she published the book : “The woman without a number”. It took her 60 years before Iby Knill could speak about her time in concentration camp Auschwitz, Buchenwald (Lippstadt) and the death march to Bergen-Belsen. When she was 75 years she decided to study theology at the University of Leeds, and when the subject of the Holocaust came up Iby Knill she expressed herself for the first time as a survivor. With the help of her professor and good friends, she found the courage to unfold her experiences and to write a book about it. In this article we have summarized a few incidents from her dramatic life story.

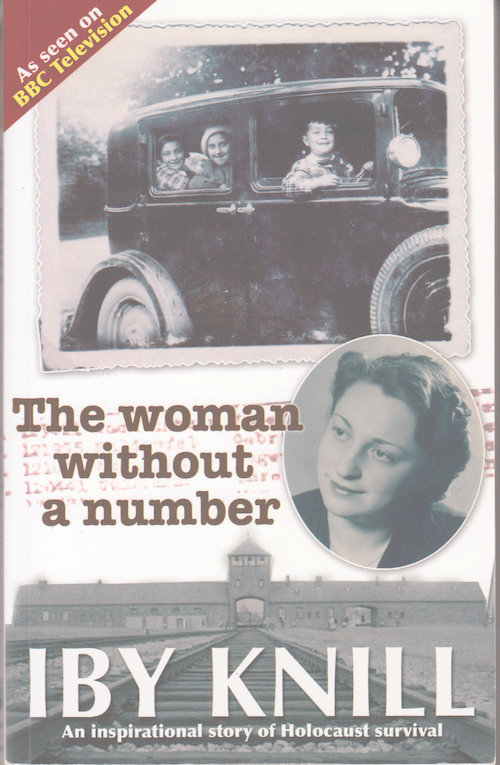

Iby Knill (MA in Theology) ‘The woman without a number’, ISBN 978-0956478764 - Book cover

Childhood and Youth

Ibolya Kaufmann, called Iby, grew up in a well-off, assimilated Jewish family in Bratislava (capital of present-day Slovakia). Her mother Irene was Slovakian, her father Beno came from Hungary. Until the early thirties of the last century, Iby born in 1923 in Kosice, enjoys a carefree childhood in the best neighbourhood of the city. The cheerful girl is an avid reader and has a talent for writing. She learns Hungarian, Slovak, Czech, German and English, five languages, which will later help her a great deal. Visits to her family in Vienna remain to exist as a cherished memory. The first shock she suffers is in 1933, when she was forced to switch from a German to a Czech school, because she is Jewish.

It gets worse after the annexation of the Sudetenland in 1938 by the Nazis and the secession from the Czech Republic. Slovakia becomes a German vassal state. In Iby’s family, religion never played a role. But suddenly she is part of a minority who are only served in stores, when no other customers are there. Iby is ashamed that she has to wear a yellow star. She tries to hide it with a scarf as much as possible on her way to school. During this time the young girl meets her first boyfriend, Nick. You can guess how short this period of happiness is. In time Nick will be one of many who do not return from the death camps.

Iby Knill at an early age

In February 1942, the mother of a same age friend calls: her daughter has just been abducted. Young Jewish girls are deported from Bratislava to the Eastern Front and are forced to be prostitutes at the disposal of German soldiers. Not one of the abductees will survive. Iby hides for a few days outside of town at a Slovak family until she disguises herself as peasant girl and in the cover of the night escapes to still fairly stable Hungary. She has to crawl through ditches and streams, being led by a paid helper. A while later that same man brings her parents over the Danube border as well. He will also guard in safekeeping belongings and photos of the family until the end of the war.

Resistance in Hungary

Iby manages to get to Budapest. Her aunt Bella lives in the Ring Street. She should offer shelter to her niece. However, fearing reprisals Bella rejects the request. Fortunately her cousin Marton, who also lives in Budapest, is willing to hide Iby in his home. The fascinating young man reveals to her soon that he belongs to the Hungarian resistance movement. He introduces his cousin to the group. From now on 18-year-old Iby helps shot-down Allied pilots to escape. She visits the Budapest spas, coffee houses and dance halls - with the aim to establish useful contacts and to gain practical knowledge. A priest, who also belongs to the resistance movement, baptizes her, gives her a New Testament and becomes an important prop and stay to her. At the end the group is busted. The young spy is threatened with torture during interrogation. The police are serious. When they pull out Iby’s right ring finger nail with pliers, her resistance is broken.

After three months the charges are dropped due to the efforts of an influential double agent. Iby is released from the women's prison in Ujpest and the others are set free as well. As soon as she has passed through the gate, she is arrested again for another reason. As a native from Slovakia she resides illegally in Hungary. She needs to go to a detention centre in the Mosonyi Street in Budapest. Due to the catastrophic hygienic conditions she gets scabies, head- and pubic lice. After her recovery the doctor teaches her some basics of nursing, skills she can use very well later on.

Iby’s situation improves and she is transferred to a refugee camp at the Szabolcs Road. There it is relatively safe. There is even a chance of being able to buy her freedom, but she lacks the necessary money. After she refuses a police officer’s directions, she is transferred to another refugee camp, far away from Budapest, in northern Hungary, where bed bugs are an ever-present plague.

There she will eventually get permission to visit her family members who are now also in Hungary as illegal immigrants residing in Budapest. Iby meets Gaspar, a friendly and good-looking 30-year-old. She falls in love with the tall dark-haired man, who seems to be immune to prosecution. He works in the film industry, which is an important industry for the war. Their wedding is planned for June 12, 1944. Gaspar wants to use everything within his power to make sure Iby is free. A marriage would give her Hungarian citizenship. She hopes that she will have nothing to fear after that.

In February 1944 Iby is paroled, but to her disappointment she cannot go to Budapest to her Gaspar, instead she must go the city of Székesfehérvár. From then on she works as a nanny for distant relatives. The German invasion of Hungary in March 1944 has no effect on their situation at first. Since she is classified by the bureaucrats (the Nazi security police) as "illegal immigrant" Iby does not need to wear a yellow star in contrast to the Hungarian Jews.

In May 1944 she walks on the street with little Gaby, one of the children, when a German patrol stops. Infuriated they ask why she was on her way without a star, while her child wears one. "I do not need one", she replies in perfect German, "I'm just the nanny." Since she cannot show any papers, she needs to go to Gestapo quarters for inspection. She claims to be Fraulein Trude, the sister of a Protestant minister from Austria. That woman was once the nanny of her little brother Tomy. Since Iby can remember many details, it is a compelling story. The Gestapo criticizes her: Why is she working for a Jewish family here, instead of being involved in Austria for her own people and leader. But for now the matter is resolved.

In Székesfehérvár she needs to report to the police every week and always with the same official who has an eye on her. One day in the early summer the policeman believes they can spend the night together. That would be of great benefit, he suggests. Later on Iby will often wonder how her life would have been, had she consented.

That same evening, on 5th June 1944, there is an air raid alarm. A few hours later, the family with whom she lives as a nanny, is torn from their sleep. The police bring all the Jews they can find together. Iby protested: She is not a Hungarian Jew, but a baptized Christian from Slovakia. It does not help. She is locked down in a brickyard and her wedding ring, money and her passport are stolen. Together with some doctors Iby tends to the sick and weak. Her planned wedding day goes by without receiving a message from Gaspar.

Auschwitz

After five days the prisoners are picked up and transported by train in cattle cars. Crowded together, their days-long journey starts. When the door opens upon arrival in Auschwitz, the unpredictable Doctor Mengele is waiting for them. After a brief inspection, he decides on life and death of the people that arrive. The sick, the elderly and the very young cannot get out. They suspect what awaits them. Their lamentations and their crying haunt Iby to the present day.

Tactfully, 20-year-old Iby survives the selection. During the journey she teamed up with two female doctors, a lady dentist and a nurse. The five women get off the train with their arms hooked and singing. Mengele is amused and points to the right to the gate with the heading: “Arbeit macht frei.”

Iby is spared the number on the left arm that is usually tattooed upon arrival. The people responsible for it are behind on schedule that day, because so many people arrived from Hungary. The "woman without number" will spend several weeks in the notorious concentration camp. Thanks to their multilingualism she can communicate with the Czech Kapos (overseers in the concentration camp) and negotiate larger food rations.

A Vatican envoy visits Auschwitz one day. In no time everyone in the barracks get better clothes. Proper tables and benches are brought in. Shortly before the Cardinal, who is escorted by Mengele, enters, the women get postcards and a pen. The command is to write home. When the Cardinal passes by, Iby speaks a few words in Latin, pretending that she is speaking to her neighbour: ‘Non quod credite videte; Ecce non est veritatem.’ (Do not believe what you see, this is not the truth). She dares to look aside and sees the surprised expression in the eyes of the Cardinal. He pauses for a moment and says a blessing for the women. As soon as he leaves again, the scenery is torn down. Cards and pens are collected. The women have to take of their clothes quickly and wear their usual prison clothes again.

The passing smoke from the crematorium smells of death. Iby is used as guinea pig for an X-ray experiment. Thanks to fortunate circumstances she must endure the procedure only once. One morning, she cannot get up; her left leg is completely stiff. She knows that if she cannot be at the mandatory roll call right away, that would be her end. The Kapo summoned orders to bring her to the hospital. This is also a death-prone place where the most vulnerable are selected daily.

A Czech doctor guards her from the worst. Before she returns to her barracks after three days, Iby receives a bracelet that identifies her as a nurse. It will help her. Days later Mengele asks for doctors and nurses at a selection role call. Iby and four companions seize this opportunity. Her job is the medical care of 525 women. Most of them are Hungarian Jews who do slave labour in a factory in Lippstadt (Germany). In the final phase of the war new labour forces are urgently needed there and they are being transferred from Auschwitz.

The five friends know that this remote site in the province of Westfalen, Germany, can be a death trap, but the chances of survival could be greater there than in the extermination camp. The evening before the departure Iby gets a visit from young twins. She knows the girls from her time as a nanny in Székesfehérvár. The 12-year-olds have witnessed how their parents had entered the gas chamber. Mengele abuses them for his twin experiments. It is clear for the both of them that they will not leave Auschwitz alive: “If the experiments are eventually completed, they will send us to the gas chamber.” The twins express a request: “Do not forget what you have experienced here and tell the world everything because we will no longer be able to do so.” A long time will pass, before Iby can fulfil her promise.

To Buchenwald (Lippstadt)

She leaves Auschwitz by train after six weeks, closely guarded. Like all the others she wears a smock with a line of yellow paint on the back. The arduous journey, with many stops on the way, takes about three days. Again and again she has the impression that she hears gunfire in the distance. On July 1944, 530 women reach Lippstadt. The camp is run under the name "SS unit I" and is a sub-camp of Buchenwald. Iby and her four companions get their own barracks and the assignment to set up a sickbay there.

Partly by chance, partly because she speaks perfect German, the commander puts Iby in charge of the small hospital. Her cousin Ella is the liaison for all German-speaking inmates. Together, the two will be able to achieve a lot in nine months for the 530 women that came from Auschwitz. The buildings of the “Lippstädt Iron and Metalworks” (LEM) are really close by. In 1944 they only produce military equipment, including ammunition, grenades, bombs and antitank guns. The women work there in twelve-hour shifts.

On November 25, Iby celebrates her 21st birthday. The others surprise her with gifts, including a miniature booklet, secretly produced in the factory with spiral binding. All the inmates signed it personally. In the evening there is even an improvised birthday cake out of bread, spread with jam and butter. The others have saved up the ingredients from their own food rations, though these were very scanty.

In late autumn the number of air raids increase. When the siren sounds, the factory needs to be evacuated. The Germans hide in the bunker, but the forced labourers have to hide in trenches. When the weather is nice, they get blankets from the barracks, make themselves comfortable and enjoy the sunshine. The women wave at the Allied aircrafts, even if the pilots probably cannot recognize them. All believe now that they will survive and long for the day of liberation.

In November 1944, more than 300 new women from Auschwitz arrive in the camp in Lippstadt, including women from France, The Netherlands, Slovakia, Greece and Romania. Iby is responsible for ensuring that of the 850 women that are in the camp, at least 95 percent work at the factory daily. In periods with low morbidity she and her fellow workers allow inmates to fake fevers. The strategy of the nurses in order to give some of the most exhausted prisoners some time off, works well for about half a year. But then they are busted and Iby is charged with sabotage of the war efforts. From now on she has to work in the factory, solely in the night shifts. She has to produce bullets for machine guns.

The Death March to Bergen-Belsen and the Liberation

From January to March 1945 several deportations to Bergen-Belsen are arranged. About 70 women are selected, especially the chronically ill. In March, there is less and less work in the weapon factory. Given the approaching Allied forces the commander instructs to evacuate the camp. They have to go to Bergen-Belsen. The long way to the concentration camp has to be made on foot. The 700 women are not allowed to take anything with them. For their poor belongings and some food supplies, the guards have constructed a handcart. The female doctors from the hospital put a bag with medical supplies on that cart during an unguarded moment. The women always have to walk during the evening. During the daytime they hide in barns and sleep on the hay. To keep the women moving, they get painful blows with a riffle butt. During the third night Iby is in great danger, her left leg is suddenly stiff – just like in Auschwitz ten months ago. Her friends take her in the middle and give her support so that she can keep going. At daybreak they hear aircraft. In the distance bombs explode. The women fervently hope that the Allies find them soon. The guards gather to discuss what they need to do. Although it is already light, they decide to continue their march. But the drone of bombers is getting closer, and the sound of battle is now to be heard. Then church bells ring. The women receive the order to lie down in the ditch. In the distance tanks emerge. In the nearby village Kaunitz white flags are hoisted. The guards try to get out and crawl towards the forest. The tanks come closer. In fact: They are Americans. The moment of liberation has come. Iby’s four companions go to the village to find suitable lodging. Meanwhile, Iby, whose left leg is still stiff, needs to rest in a farmhouse, where a white flag is waving. The family is sitting at the breakfast table. The unexpected guest with the emaciated body settles down on the sofa. The mother whispers something to her young daughter. The girl gets up, goes to the stranger and offers her a dark brown egg. "It is Easter Sunday”, said the child.

After the war

Later Iby arrives in a hospital in Bielefeld (Germany). After her recovery, she joined the British military administration as a translator. There she meets Bert Knill, an English officer. Then Iby learns about the fate of her family. Her mother survived Auschwitz; her father was murdered shortly before the liberation in the gas chamber. Neither Iby’s first boyfriend Nick, nor her cousin Matron, nor her former fiancé Gaspar survived the war. Her generation is almost completely extinguished. She wants to start a new life elsewhere. She says yes to Bert's marriage proposal. Her wedding will be in December. However, in September 1946, she returns to her family in Bratislava first, where she sees her brother Tom again. Three months later Iby moves with Bert to England. She does not share anything with his family about the concentration camps. At first she is afflicted of nervous breakdowns in her new home country. She decides to push the past away, both the good and the bad things that happened. For a long time she is unable to speak and understand German. The couple has two children, Chris and Pauline. Iby is a loving mother, but as a result of her experience, she has trouble to allow feelings. Suppressing her feelings seems to work, she has a successful career, working in education first, and later as a designer. In 2002 when she is nearly 80-years-old, she begins to write down her memories for her grandchildren Julia, James and Katarina. In 2010 she published her records as “The woman without a number.” A TV-station produces a documentary entitled "My Story". For this program she returns to Kaunitz in May 2010.

Iby Knill (l.) und Marie-Louise Weissenböck (r.). am 12-09-2015 © Hans Weissenbock.

Meanwhile Iby Knill is 91 and active in the Holocaust Survivors Friendship Association. So for several years now she travels across the UK to talk mainly with young people. She believes she was lucky to survive, because of the following reason. To be a witness of everything she experienced. She has learned from personal experience to which destructive consequences prejudice, intolerance and hatred can lead.

From:

Iby Knill (MA in Theology) ‘The woman without a number’, ISBN 978-0956478764

Blicker, City Magazin from Lippstädt. Christoph Motog: ‘Die Frau ohne Nummer’